Netflix - Quantity, quality, and the paradox of choice

I have been disappointed with Netflix lately. After they delisted a few of my favourite shows (especially Doctor Who), and I struggled to find anything new and good to watch, I started wondering if the Netflix Overlords had made a strategic decision to offer cheaper, lower quality, but more variety of content to hopefully satisfy us through their machine learning algorithms finding just the right show for an individual, as opposed to focusing on making brilliant shows for all to enjoy. I was (somewhat) wrong!

Note: This post was published and editorialised by Medium: See the editorialised version here.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to obtain data of all the externally produced shows Netflix offered, year by year. Fortunately, this is available for Netflix originals, from Wikipedia, and the show ratings are available from IMDb. Note that these are not just series - the shows include movies, documentaries, mini-series, etc.

What we encounter in the data was certainly a lesson for me, and maybe an insight on the psychology of choice applied to how we should pick Netflix shows.

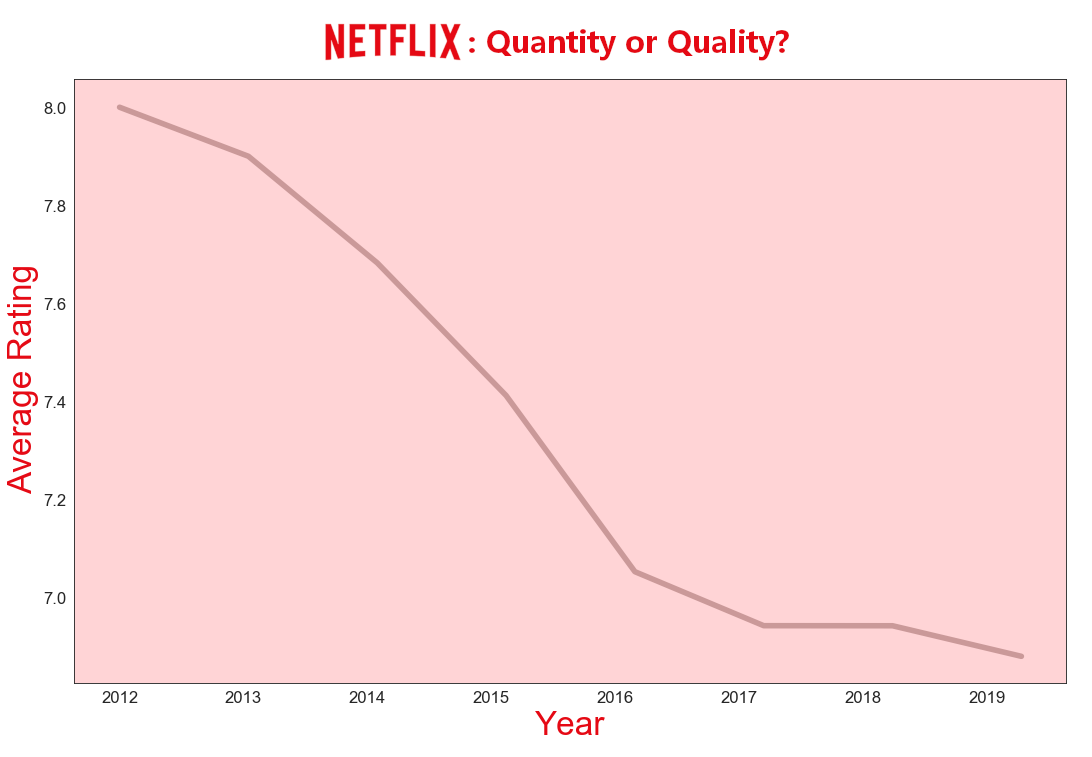

Initially, we can look just at the mean (average) rating. This tells a sad story. Things started out with a bang - just one option, but a good show with a rating of 8. Now, the average show weighs in at 6.8. Maybe the typical show is good enough to watch, but certainly not worth your time given the amount of outstanding content out there.

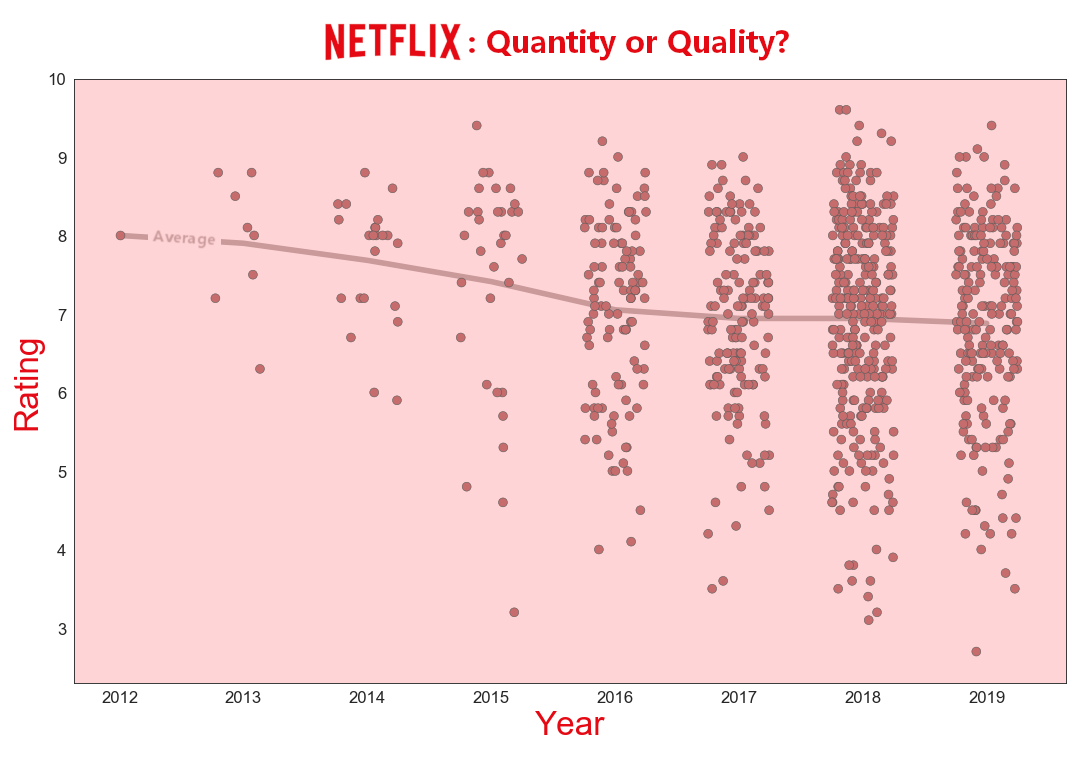

However, this graph doesn’t tell the whole story. In fact, it’s misleading. If we rather look at individual shows, we see that the amount of quality Netflix original offerings is actually increasing. There are far more and more excellent shows out there than before. You just have to sift through Netflix’s suboptimal recommendations algorithm to find them. 2018, in particular, was an excellent year. You could watch 6 new shows with a rating over 9!

How does this link to our psyche, though?

Barry Schwartz, in his book The Paradox of Choice, explains how an increase in the amount of options available to us actually results in us being unhappier. The average person certainly seems less unhappy with Netflix [citation: see below graph].

This unhappiness is due an unfortunate combination of reasons:

- We have a choice to make. Rather than how we or our parents previously had to watch the one and only movie on the only TV channel on Sunday at 8pm, we now have the amazing ability to pick from this huge plethora of movies. However, we also have to take mental responsibility for our options rather than just blaming the TV channel for their crappy taste in movies. This responsibility means that we beat ourselves up for picking the wrong movie. Especially if others are influenced by our decision: Interestingly, it’s proven that if we’re picking an option for others, we beat ourselves up more than if it was just for ourselves.

- Decisions are harder with more options, and mistakes are more likely. We take longer to make the decision. So not only are we angry with ourselves (or Netflix) for picking the wrong option, but we also beat ourselves up more for the 30 minutes we took to pick the wrong show to watch on date night. All of this while the food got cold and the boyfriend got restless.

- When ruminating on our mistakes, we imagine the perfect alternative and set our expectations to that. This is called “counterfactual thinking.” What if a series existed that had the hype of Game Of Thrones Season 1, the thrill of House of Cards, and the quality jokes from Better off Ted? Obviously this show is an impossibility, but our brains just work this way - constructing the dream alternative.

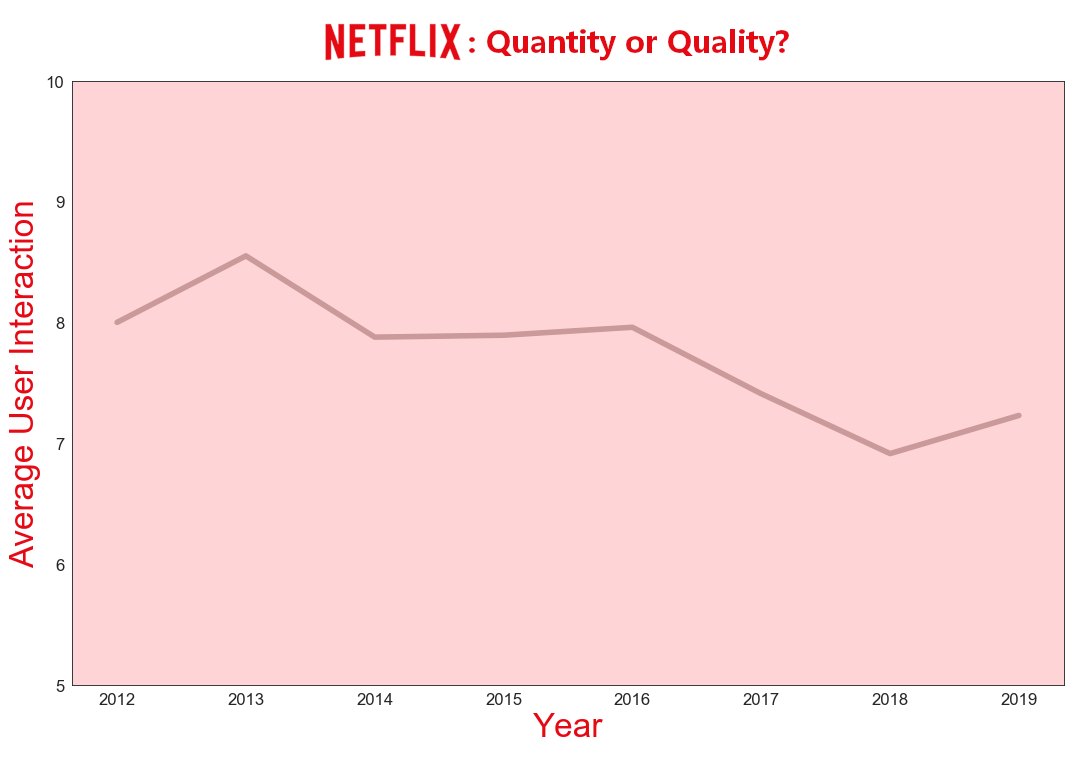

But this is all just theory. Can we prove that people are unhappier with Netflix? Yes. I looked at the average user interaction with Netflix - the average rating posted on IMDb for any Netflix show, year on year. Just to reiterate, this isn’t averaged by show. What we see here is the average vote someone gives any Netflix show.

It’s not a massive change, down from a peak if 8.6 to a trough of just under 7, but remember that this is representing hundreds of millions of votes. This is a lot of cumulative enjoyment: so it’s quite clear that people are unhappier with Netflix shows (Or maybe with shows in general!) What really sticks out here, though, is that the year with the most highly rated shows - 2018 - corresponded with the unhappiest users. Fortunately, things have perked up in 2019. Maybe Netflix’s algorithms are actually working, delivering us content better suited to us. Or maybe we’ve learnt how to pick shows for ourselves.

So what advice would Barry Schwartz and his sources give to Netflix? Probably to reduce the amount of options they put out, or at least reduce the options they show to you, the viewer. Netflix absolutely do this to some extent. He would probably also tell them to cool it on trying to suggest movies and shows by the optimum category that their algorithm decided for the user, but rather do suggestions more by rating. Because, to put it frankly, they are suggesting utter rubbish to us when there are really high rated shows hidden behind the fold or a few clicks away. If they want to keep us for the long term, they need to improve our average interaction with them, as shown in the last graph.

And what advice does Barry give to us? He, and other psychologists, recommend a really simple approach: Pick a good enough show, based on whatever category or rating system you think is best for you, and don’t look back. It’s proven that you’ll be more satisfied with Netflix if you, for instance, decide that any thriller movie or series with an 8 rating on IMDb deserves to be watched. You then pick the first option on Netflix that you haven’t seen, and you enjoy it, not regretting about what else you could have done with your time, or not picking the optimal option. You stay grateful for the fact that you got on-demand, self-chosen content streamed directly to you, rather than being forced to watch the original Home Alone on your local TV channel for the third time.

Of course, this way of thinking applies to other areas. Did you pick the right job? Are you living in the correct city? Should you really have bought a purebred black Pug, or was a more conventional colour the correct choice? If you are interested, I highly recommend giving The Paradox of Choice a read.

Code and tools

Code: GitHub

Data: Wikipedia show list and IMDb ratings

Tools: Python, GIMP