Natural Language Processing - Emotion Detection with Multi-class, Multi-label Convolutional Neural Networks and Embedding

I came across a well-prepared dataset provided by Google, with 58 000 ‘carefully curated’ Reddit comments, labeled with one or more of 27 emotions, e.g. anger, confusion, love. Google had used this to train a BERT model, in which they had varying success in emotion detection depending on the type of comment. I thought it would be a great example to learn how to tweak Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Embedding to a Natural Language Processing (NLP) problem, and obtained decent accuracy for some emotions, but not as good of course as Google’s BERT.

This is not a tutorial - there are plenty of great tutorials on CNNs and Embedding out there. Instead, this is rather a complete code example, tackling multi-class multi-label classification, which was rather hard to find complete & free examples for.

Spoiler: My code doesn’t do as well as Google, who also provide their code in the above link. Their well-oiled BERT solution obtains around 46% F1 score, while I only obtain 42%. However, I didn’t spend too much time optimising my model, so there might easily be another 2 or 3 percent available through some optimisations.

More on the GoEmotions dataset

Firstly, kudos to the Google research team (actual paper here) for such a well-prepared and cleaned dataset, which you can obtain from the link.

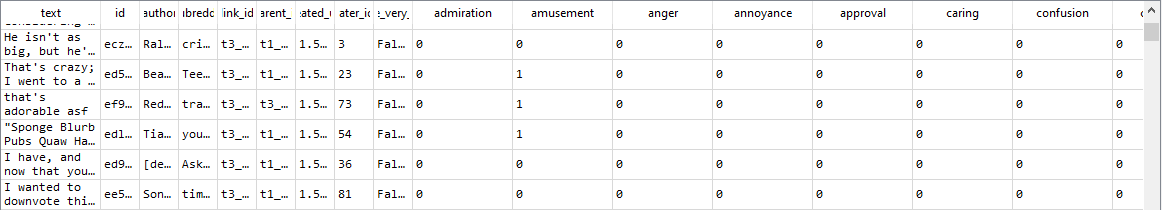

The dataset, along with some other metadata, provides a reddit comment (“text”), along with a corresponding set of emotion labels:

Starting intuition

This is a complicated domain - different users display sentiment in different ways, and many of these comments are very short and contain two meanings, e.g. “That’s adorable asf” Secondly, some comments, such as “This video doesn’t even show the shoes he was wearing”, are completely neutral and labelled as such.

However, there are definitely clearly words and phrases which are giveaways to certain emotions. Some, such as love or excitement, are probably quite easy to detect. However, subtle emotions such as pride or curiosity, less so. So I expect to get some success, but certainly don’t expect to do better than Google. After all, these comments aren’t responses to “How do you feel?” - they are seemingly arbitrarily picked from reddit.

The code, explained

The python code obtaining 42% F1 score on the dataset is here. Once you obtain the dataset from Google, you can run it out of the box just by changing the path to the datasets, assuming you have all dependencies installed. However, training the Neural Network will take about 30 minutes to train on 15 epochs depending on your computing power.

Below, I’ll describe each section, excluding the imports.

Fetching the data

This is standard. We are fetching the data CSVs (which are separate by Google’s design), concatenating them, and choosing our input vector, X, and binary output, y. We are then splitting the data into training and test data. The dataset is very large - almost 20,000 comments. Therefore, many other train_test_split splits would have worked, too, but we can go with the standard practice.

df1 = pd.read_csv('../../data/emotions/goemotions_1.csv')

df2 = pd.read_csv('../../data/emotions/goemotions_2.csv')

df3 = pd.read_csv('../../data/emotions/goemotions_3.csv')

frames = [df1, df2, df3]

df = pd.concat(frames)

X = df['text'].values

X= X.astype(str)

y = df.iloc[:,9:].values

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X,y,test_size=0.2)

After this, we now have roughly 20,000 mappings of comments (“I really love bitterballen!”) with their associated labelled emotions (admiration, amusement, anger, annoyance, approval, caring, confusion, curiosity, desire, disappointment, disapproval, disgust, embarrassment, excitement, fear, gratitude, grief, joy, love, nervousness, optimism, pride, realization, relief, remorse, sadness, surprise).

Tokenizing the data

In order to provide a valid input to the neural network, we need to tokenize each word in each row of the data. This means that rather than a word, we’ll have a mapping to a giant dictionary of Token:Word, e.g. a sentence “I really love bitterballen!” would tokenize 1:”i”, 2: “really”, 3: “love”, 4:”bitterballen”

Side note: Right away, there’s an improvement that could be made here, that I lose out on: The exclamation mark, or capitalisation of text, could be used to predict some strong emotions.

Rather than now represent each sentence in text, it would be a vector: [1, 2, 3, 4]. A second sentence “Bitterballen love really I!” would now vectorize to [4, 3, 2, 1], and a sentence with new words would add new values [5, 6, …] to the token list.

- num_words is the amount of words in the dictionary. This was chosen by looking at the tokenizer results. After the first 9000 most occuring words in the dataset, we start to hit typos, strange acronyms and words that are only used once. These aren’t useful to train the network, so they should be discarded. The result of this is that the amount of words covered by the word embedding (section below), increases from 51% to 95%. We are now working with a good corpus of words that are well-known by word embeddings, therefore mostly commonly used words but with 5% of words that might be reddit specific, hence great for training the network.

- Here, there is also a two row workaround in manually setting the tokenizer’s word index, resolving a known issue with Tokenizer. This does not affect the model output, but does make training time remarkably faster because it manually reduces the tokenizer size to 9000.

- maxlen is the maximum length of the input text from reddit. For our algorithm, we need each post to be a list of tokens of equal length. For instance, if maxlen was 10, a short post of only 5 words would be padded with zeroes: [1 52 3 10 3 0 0 0 0 0], whereas a long post of 15 words would be limited to 10. Here, I have gone with 20 just for safety sake.

tokenizer = Tokenizer()

tokenizer.fit_on_texts(X_train)

#https://www.kaggle.com/c/jigsaw-unintended-bias-in-toxicity-classification/discussion/91240

num_words=9000

tokenizer.word_index = {e:i for e,i in tokenizer.word_index.items() if i <= num_words} # <= because tokenizer is 1 indexed

tokenizer.word_index[tokenizer.oov_token] = num_words + 1

X_train = tokenizer.texts_to_sequences(X_train)

X_test = tokenizer.texts_to_sequences(X_test)

vocab_size = len(tokenizer.word_index) + 1 # Adding 1 because of reserved 0 index

maxlen = 20

X_train = pad_sequences(X_train, padding='post', maxlen=maxlen)

X_test = pad_sequences(X_test, padding='post', maxlen=maxlen)

Embeddings

By tokenizing, we turn each row into a more mathematical vector of words, e.g. [1 52 3 10 3 0 0 0 0 0]. Being a vector, this is something that we can use as input to a ML model. However, there is an even better way to represent the data.

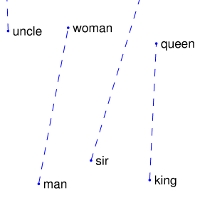

Embeddings are large pre-trained mappings of related words in an n-dimensional space. For example, as shown below, if we trained a word association model on a large amount of texts, one dimension of associated words it would pick up are on gender. In this dimension, the embedding would be a simple vector indicating that “Man is to woman” as “king is to queen.” When using an embedding, you enable the model you train to quickly make these distinctions. This helps the model train faster and more effectively, eliminating the confusion that synonyms and more abstract text would create. Your model can be more efficiently trained to consider these words x% similar, and produce similar outputs. For a more intuitive, in-depth explanation, try Will’s.

So imagine this image, but with 50 to 300 dimensions. Gender, colour, mood, and so on. That’s what Stanford’s Glove library provides, and is the embedding source used in this example. Google’s BERT uses pre-trained embeddings, too.

In the code below, there is a function create_embedding_matrix to process the embedding file into a matrix. This is shamelessly obtained from an excellent tutorial on text classification with keras.

def create_embedding_matrix(filepath, word_index, embedding_dim):

vocab_size = len(word_index) + 1

embedding_matrix = np.zeros((vocab_size, embedding_dim))

with open(filepath,encoding='utf-8') as f:

for line in f:

word, *vector = line.split()

if word in word_index:

idx = word_index[word]

embedding_matrix[idx] = np.array(

vector, dtype=np.float32)[:embedding_dim]

return embedding_matrix

embedding_dim = 300

embedding_matrix = create_embedding_matrix('../../data/embedding/glove/glove.6B.300d.txt', tokenizer.word_index, embedding_dim)

nonzero_elements = np.count_nonzero(np.count_nonzero(embedding_matrix, axis=1))

embedding_accuracy = nonzero_elements / vocab_size

print('embedding accuracy: ' + str(embedding_accuracy))

Here, there are only two choices to explain:

- The embedding package to use. I tried Glove and Fasttext. Both produced similar results, but Glove’s was slightly better, even with fewer dimensions.

- embedding_dim is the amount of dimensions of word relations to consider. Glove has options from 50 through to 300. Using 50 really sped up training, but 300 provided a 2% improvement in F1 score for me.

So, as a result of embedding, rather than an input array mapping some sentences to text

[1 52 3 10 3 0 0 0 0 0]

We instead have a huge matrix mapping each word to dimensional values! So rather than just a list of words, we essentially have a matrix of meanings for each word in our corpus.

[0 dim_1 dim_2 ... dim_n

1 dim_1 dim_2 ... dim_n

2 dim_1 dim_2 ... dim_n

...

9000 0 0 ... 0 ]

with each dim_ value being an actual representation of that word’s value in a dimension, e.g. gender.

[0 0.1 0.8 ... 0.5

1 0.3 0.2 ... 0.0

2 0.0 0.4 ... 0.1

...

9000 0 0 ... 0 ]

The neural network

model = Sequential()

model.add(layers.Embedding(vocab_size, embedding_dim, weights=[embedding_matrix], input_length=maxlen, trainable=True))

Firstly, we add an embedding layer to accept the embedding matrix we just made. Trainable = True here because 1. the Glove embedding is not trained on the last 5% of words in our corpus, which may be super useful for the model and 2. There might be differences in embedding dimensions in reddit language use, which can be modified in real-time while training.

model.add(layers.Conv1D(256, 3, activation='relu'))

Secondly, a convolutional layer to turn this into a CNN. This essentially behaves as a sliding layer of 3 words looking for 256 different filters. In other words, it trains the model to look for 256 different ‘meanings,’ sliding over the text bit by bit. Whilst I did try different values for both, this amount worked well probably because:

- 256 filters is close to the 300 dimensions used

- 3 words is a good average amount of words to discern an emotion from in the input data

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

A dropout layer (Here, a regularizer would have been an option too). I found that the network, with such a large dataset, was overfitting right after one epoch. To prevent this, the dropout layer simply deactivates a random 20% of the nodes per batch, making sure we don’t rely too much on one node in the network. This decreases overfitting, and most models now do their best after around 10 epochs as opposed to 1. This works hand-in-hand with learning rate, and the amount of epochs chosen.

model.add(layers.GlobalMaxPooling1D())

This is standard practice in CNNs, now reducing the amount of incoming feature vectors, taking only the maximum ones for each dimension.

model.add(layers.Dense(112, activation='relu'))

model.add(layers.Dense(28, activation='sigmoid'))

opt = optimizers.Adam(lr=0.0002)

model.compile(optimizer=opt, loss='binary_crossentropy')

model.summary()

Again, standard practice to have another small dense relu layer before a sigmoid output layer for classification. Finally, the model is combined with an adam optimizer and binary_crossentropy loss function, both which are your bread and butter for binary classification neural networks, and also for multi-label, multi-class classification. A learning rate of 0.0002 was chosen through trial and error. As mentioned above, you can play around with this, the amount of epochs, and the dropout rate to affect the speed of the network’s learning, overfitting, and overall end result.

callbacks = [EarlyStopping(monitor='val_loss', patience=2),

ModelCheckpoint(filepath='best_model.h5', monitor='val_loss', save_best_only=True)]

res = model.fit(X_train, y_train, epochs=15, verbose=True, callbacks=callbacks, validation_data=(X_test, y_test), batch_size=100)

*Now we add some callbacks to allow us to go back to the best model, and stop training soon, if the neural network starts getting worse with training. *The batch size of 100 was also found through trial and error.

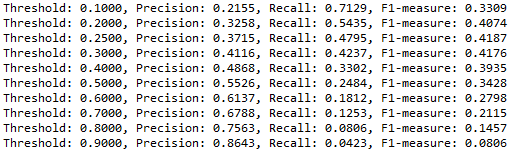

Picking a sigmoid threshold

thresholds=[0.1,0.2,0.25,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8,0.9]

for val in thresholds:

pred=y_pred.copy()

pred[pred>=val]=1

pred[pred<val]=0

precision = precision_score(y_test, pred, average='micro')

recall = recall_score(y_test, pred, average='micro')

f1 = f1_score(y_test, pred, average='micro')

print("Threshold: {:.4f}, Precision: {:.4f}, Recall: {:.4f}, F1-measure: {:.4f}".format(val, precision, recall, f1))

This outputs the precision and recall, and resultant F1 score (mean of precision and recall) for each threshold. We could be even more fancy here, and optimise a threshold for each emotion, depending on the exact emotion we wanted to detect. But I don’t.

Results

After a modest 12 epochs, the network optimises its loss function, and we obtain an F1 score of almost 42%.

Using the above threshold loop, it looks like at a threshold of 0.25, we get the optimal F1 score:

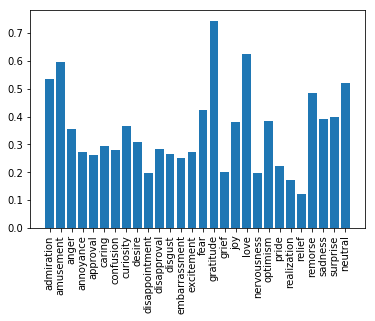

Using this threshold of 0.25, we can determine the F1 score for each individual emotion:

column_names = list(df.columns[9:])

threshold = 0.25

for i in range(0,27):

emotion_prediction = y_pred[:,i]

emotion_prediction[emotion_prediction>=threshold]=1

emotion_prediction[emotion_prediction<threshold]=0

emotion_test = y_test[:,i]

precision = precision_score(emotion_test, emotion_prediction)

recall = recall_score(emotion_test, emotion_prediction)

f1 = f1_score(emotion_test, emotion_prediction)

print("Emotion: {}, Precision: {:.4f}, Recall: {:.4f}, F1-measure: {:.4f}".format(column_names[i], precision, recall, f1))

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure()

plt.bar(column_names,f1_scores)

plt.xticks(rotation=90)

plt.show()

Some interesting results here, when graphing emotions’ F1 scores:

As anticipated, some emotions (amusement, gratitude, love) are way easier to predict than subtle emotions like disappointment, realization, relief.

Taking this model further

As mentioned through the writeup, there are several ways we could improve on this model:

- Using a grid search to tweak the parameters (especially learning rate, dropout, convolutional hyperparameters)

- Optimising the sigmoid threshold for each emotion, as opposed to the entire network’s output

- Gleaming more information from exclamation marks, all-caps words, etc.

- Copy pasting Google’s BERT-based code :)